Register with us

Oops! Something went wrong while submitting the form.

Welcome

Hi human, you are not logged in.

Oops! Something went wrong while submitting the form.

The Behavioral Barometer

The latest and greatest from your human experience guides at Element Human

When it comes to both ads and advertising effectiveness, there's more to it than meets the eye. Attention metrics and measurement are just the first chapter.

In the world of advertising, attention has become a major focus. We often assume that if an ad grabs someone's attention, it will be effective. But is attention the only thing that matters? This post explores the role of attention in advertising, where it came from, how we measure it, and where it fits within the larger picture of advertising effectiveness.

We'll look at historical crises that shaped our understanding of advertising, research from unexpected sources, and data that challenges common assumptions.

Before recent events, the advertising industry faced several crises that pushed us to rethink what makes an ad successful. These crises led to a greater focus on accountability and measurement.

One of the first major problems was the "viewability crisis." Advertisers realized that many of the ads they paid for were never actually seen. This was because ads were counted as "served" even if they were located at the bottom of a webpage and a user never scrolled down to see them.

Brands and agencies became concerned that they were wasting their advertising budgets on ads that no one was viewing. This led to demands for better measurement and accountability. Technology stepped in to solve this problem, giving us viewability metrics that tell us what percentage of served ads were actually in view.

Even with viewability solved, a new problem emerged: just because an ad was in view didn't mean anyone was actually looking at it. This led to the rise of attention metrics, using eye-tracking technology. These metrics measured whether people were actually looking at the ads on the screen.

Attention providers used eye-tracking to determine the percentage of the audience that was actually looking at an ad. This development pushed brands and agencies to demand even more measurability. Viewability and attention became better understood, but a critical question remained: Is that enough to guarantee advertising effectiveness?

The central question is this: Does an ad that is seen actually have an impact on the audience? Does it lead to changes in attitude or, ultimately, to action?

Does it lead to changes in attitude or, ultimately, to action?

Many in the industry assume that more attention leads to better impact and better outcomes. But is this always the case? We need to explore this assumption and examine the evidence.

The Sesame Workshop, the creators of Sesame Street, conducted research on their shows. They wanted to ensure their content was engaging and educational for children. Their research revealed some surprising insights about attention.

The Sesame Workshop developed a method called the "distractor technique." They would show an episode of Sesame Street to a group of children in a room. At the same time, they would introduce distractions, such as another screen showing different content. Researchers then coded how distracted the children became while watching the show. This helped them assess whether the show was holding the children's attention effectively.

The researchers divided the children into two groups. One group watched the show with no distractions. The other group watched with distractions. As expected, the group with distractions showed lower levels of attention. However, when the researchers tested both groups on their comprehension of the show, they found something unexpected. Both groups comprehended the material equally well.

The study concluded that "children's intake of a program's message is not proportionately related to their attention to the screen." Even though the children in the distraction group paid less visual attention, they still understood the show's message.

This finding has important implications for advertising effectiveness. An advertisement is essentially a condensed program with its own message. We pay attention not only with our eyes but also with our ears. Even if we look away from the screen, we may still be listening and absorbing the message. We listen for cues that might make us look back at the screen.

The study analyzed 74 videos across 37 brands with 17,544 participants to understand what makes ads successful on Twitch. It examined memory, emotion, and self-reported responses using methods like facial coding, eye-tracking, and implicit association tests.

In 2019, BBC Global News conducted research into podcast sponsorships. There was a common belief that people who listen to podcasts are too active to pay attention to ads. People often listen to podcasts while driving, running, or doing chores. The BBC wanted to investigate whether this activity detracted from brand messaging.

The BBC used neuroscience to explore this question. They found that being active while listening actually enhanced attention to the programming and brand messages. People were more likely to pay attention and listen for longer when their hands were busy. It seemed that doing something else allowed them to absorb the message more easily.

The BBC's "Audio Activated" study demonstrates that apparent distractions can actually increase engagement. Attention is not solely visual.

This suggests that when people listen without any distractions, they may be more likely to critically evaluate the message. When they are engaged in an activity, they may lower their cognitive barriers and allow the message to wash over them.

"Conceptual closure" is a neuroscience term. It refers to the idea that people need "gaps" in information to process what they have seen and store it in their memory.

A 2023 Thinkbox study using neuro-insight explored this concept. They found that moments signaling the end of a storyline or message allow the brain to process and store the information. During these moments, people may not be able to take in new information. This reinforces the idea that looking away is a natural and necessary part of absorbing a message. Ads need to be mindful of these moments of conceptual closure.

The BBC's podcast research also revealed another interesting finding: Words used in podcasts can become associated with the sponsoring brand. For example, if a finance podcast frequently mentions the word "innovative," that word can become linked to the finance brand sponsoring the podcast. This can happen even if the brand is never explicitly described as innovative. The implicit association can still benefit the brand.

At Element Human, we measure attention, emotion, memory, and brand uplift. We wanted to test whether more attention actually leads to better results for brands.

We analyzed 600 randomly selected tests from our system. We looked at the relationship between attention (measured in seconds spent) and brand awareness uplift. The correlation coefficient was 0.3, which indicates a weak correlation. A coefficient of 0.5 or higher would be considered a moderate to strong correlation.

Our analysis revealed two key observations:

These findings suggest that attention alone is not a reliable predictor of brand awareness. It's certainly not the only thing that drives engagement or purchase.

Element Human uses "attention curves" to benchmark attention. These curves show how attention typically declines over time for different types of ads. By comparing an individual ad's performance to the attention curve, we can identify ads that "buck the curve"—that is, perform better than expected at certain points.

Understanding why an ad bucks the curve can provide valuable insights. For example, if a brand is mentioned at the end of an ad when attention is high, that's a positive sign. But if the brand is mentioned when attention is at its lowest, that's a problem. A single attention score isn't enough to tell the whole story. We need a deeper analysis of what's happening at different moments in the ad.

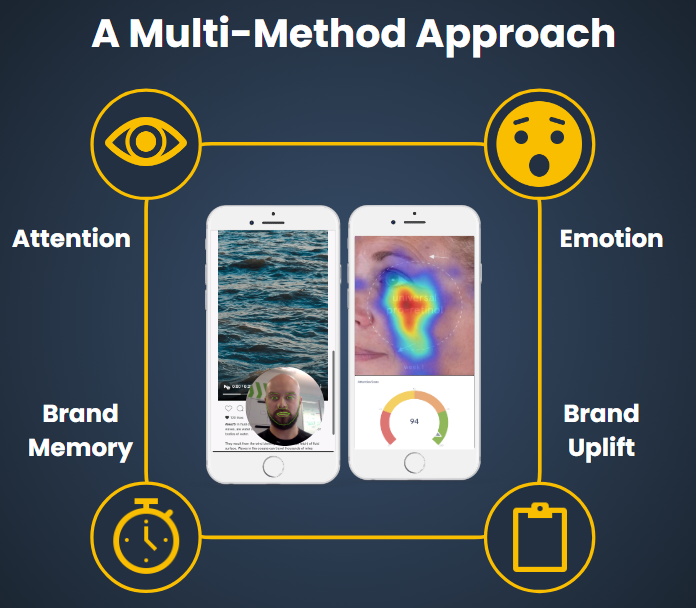

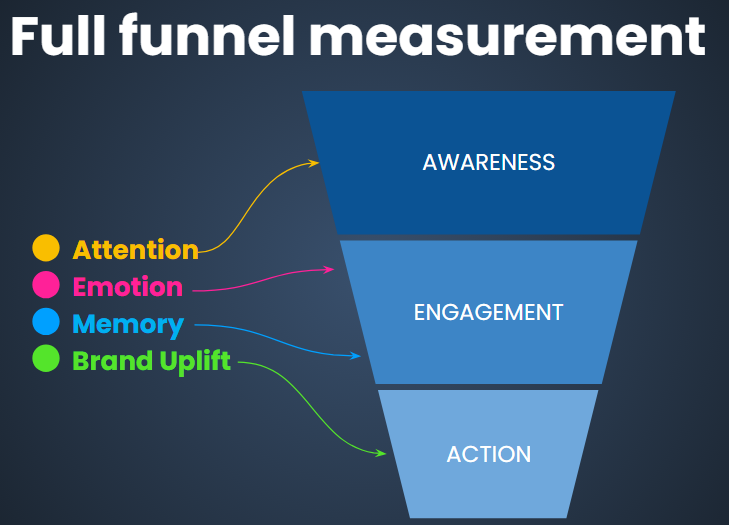

Element Human uses a multi-method approach. We combine attention data with measures of emotion, brand memory, and brand uplift. This gives us a complete view of how a campaign is performing. We can see how ads perform across all platforms. This provides a full-funnel view, from initial awareness to final action.

Attention is important, but it is not the only factor that determines advertising effectiveness. It is a critical component of success. Think of it as a starting point, not the complete picture. To fully understand advertising effectiveness, we need to look beyond attention. We must understand how ads cut through the noise, how they are encoded in memory, and how they drive purchase behavior.

"You guys are excellent partners, and we appreciate the innovativeness."

"We are proud to partner with Element Human to delve even deeper into the emotional impact of creator content on audiences and offer actionable insights, empowering brands to maximise the impact of their influencer marketing campaigns."

"You are leading the way! A pleasure to work with your team."

"Element Human has been an invaluable partner in showing the business impact creators can have on brand performance."

"They’re responsive, collaborative, and genuinely invested in our success, a rare combination that has made them a trusted partner of mine across multiple companies."

"We were amazed at what we achieved in such a condensed time frame"

"Creator Economy PSA... Vanity metrics surpassed long ago. Effectiveness, impact and ROI are all measurable with partners like Nielsen, Element Human and Circana."

"Element Human was not just key for the BBC’s project but also was engaging and a great learning experience for me personally!"